Understanding the New Nonprofit Accounting Standard

By Charles Hall | Accounting

Are you ready to implement FASB’s new nonprofit accounting standard? Back in August 2016, FASB issued ASU 2016-14, Presentation of Financial Statements of Not-for-Profit Entities. In this article, I provide an overview of the standard and implementation tips.

New Nonprofit Accounting – Some Key Impacts

What are a few key impacts of the new standard?

- Classes of net assets

- Net assets released from “with donor restrictions”

- Presentation of expenses

- Intermediate measure of operations

- Liquidity and availability of resources

- Cash flow statement presentation

Classes of Net Assets

Presently nonprofits use three net asset classifications:

- Unrestricted

- Temporarily restricted

- Permanently restricted

The new standard replaces the three classes with two:

- Net assets with donor restrictions

- Net assets without donor restrictions

Terms Defined

These terms are defined as follows:

Net assets with donor restrictions – The part of net assets of a not-for-profit entity that is subject to donor-imposed restrictions (donors include other types of contributors, including makers of certain grants).

Net assets without donor restrictions – The part of net assets of a not-for-profit entity that is not subject to donor-imposed restrictions (donors include other types of contributors, including makers of certain grants).

Presentation and Disclosure

The totals of the two net asset classifications must be presented in the statement of financial position, and the amount of the change in the two classes must be displayed in the statement of activities (along with the change in total net assets). Nonprofits will continue to provide information about the nature and amounts of donor restrictions.

Additionally, the two net asset classes can be further disaggregated. For example, donor-restricted net assets can be broken down into (1) the amount maintained in perpetuity and (2) the amount expected to be spent over time or for a particular purpose.

Net assets without donor restrictions that are designated by the board for a specific use should be disclosed either on the face of the financial statements or in a footnote disclosure.

Sample Presentation of Net Assets

Here’s a sample presentation:

| Net Assets | |

| Without donor restrictions | |

| Undesignated | $XX |

| Designated by Board for endowment | XX |

| XX | |

| With donor restrictions | |

| Perpetual in nature | XX |

| Purchase of equipment | XX |

| Time-restricted | XX |

| XX | |

| Total Net Assets | $XX |

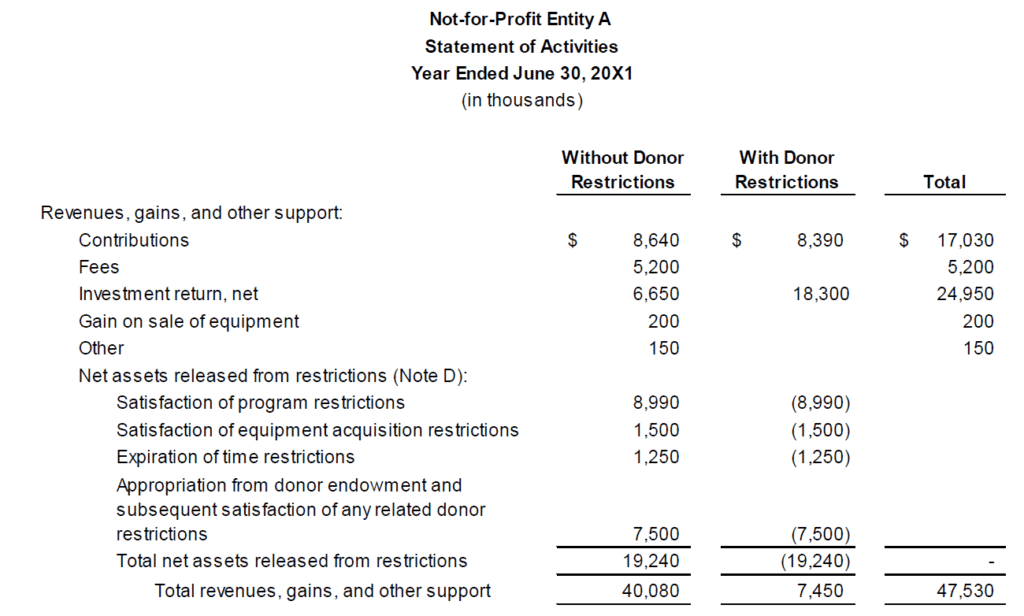

Net Assets Released from “With Donor Restrictions”

The nonprofit should disaggregate the net assets released from restrictions:

- program restrictions satisfaction

- time restrictions satisfaction

- satisfaction of equipment acquisition restrictions

- appropriation of donor endowment and subsequent satisfaction of any related donor restrictions

- satisfaction of board-imposed restriction to fund pension liability

Here’s an example from ASU 2016-14:

Presentation of Expenses

Presently, nonprofits must present expenses by function. So, nonprofits must present the following (either on the face of the statements or in the notes):

- Program expenses

- Supporting expenses

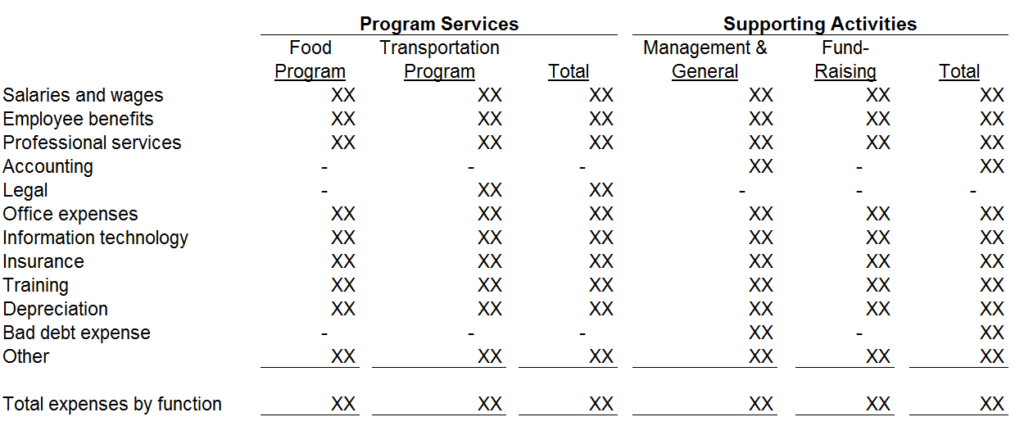

The new standard requires the presentation of expenses by function and nature (for all nonprofits). Nonprofits must also provide the analysis of these expenses in one location. Potential locations include:

- Face of the statement of activities

- A separate statement (preceding the notes; not as a supplementary schedule)

- Notes to the financial statements

I plan to add a separate statement (like the format below) titled Statement of Functional Expenses. (Nonprofits should consider whether their accounting system can generate expenses by function and by nature. Making this determination now could save you plenty of headaches at the end of the year.)

External and direct internal investment expenses are netted with investment income and should not be included in the expense analysis. Disclosure of the netted expenses is no longer required.

Example of Expense Analysis

Here’s an example of the analysis, reflecting each natural expense classification as a separate row and each functional expense classification as a separate column.

The nonprofit should also disclose how costs are allocated to the functions. For example:

Certain expenses are attributable to more than one program or supporting function. Depreciation is allocated based on a square-footage basis. Salaries, benefits, professional services, office expenses, information technology and insurance, are allocated based on estimates of time and effort.

Intermediate Measure of Operations

If the nonprofit provides a measure of operations on the face of the financial statements and the use of the term “operations” is not apparent, disclose the nature of the reported measure of operations or the items excluded from operations. For example:

Measure of Operations

Learning Disability’s operating revenue in excess of operating expenses includes all operating revenues and expenses that are an integral part of its programs and supporting activities and the assets released from donor restrictions to support operating expenditures. The measure of operations excludes net investment return in excess of amounts made available for operations.

Alternatively, provide the measure of operations on the face of the financial statements by including lines such as operating revenues and operating expenses in the statement of activities. Then the excess of revenues over expenses could be presented as the measure of operations.

Liquidity and Availability of Resources

FASB is shining the light on the nonprofit’s liquidity. Does the nonprofit have sufficient cash to meet its upcoming responsibilities?

Nonprofits should include disclosures regarding the liquidity and availability of resources. The purpose of the disclosures is to communicate whether the organization’s liquid available resources are sufficient to meet the cash needs for general expenditures for one year beyond the balance sheet date. The disclosure should be qualitative (providing information about how the nonprofit manages its liquid resources) and quantitative (communicating the availability of resources to meet the cash needs).

Sample Liquidity and Availability Disclosure

The FASB Codification provides the following example disclosure in 958-210-55-7:

NFP A has $395,000 of financial assets available within 1 year of the balance sheet date to meet cash needs for general expenditure consisting of cash of $75,000, contributions receivable of $20,000, and short-term investments of $300,000. None of the financial assets are subject to donor or other contractual restrictions that make them unavailable for general expenditure within one year of the balance sheet date. The contributions receivable are subject to implied time restrictions but are expected to be collected within one year.

NFP A has a goal to maintain financial assets, which consist of cash and short-term investments, on hand to meet 60 days of normal operating expenses, which are, on average, approximately $275,000. NFP A has a policy to structure its financial assets to be available as its general expenditures, liabilities, and other obligations come due. In addition, as part of its liquidity management, NFP A invests cash in excess of daily requirements in various short-term investments, including certificate of deposits and short-term treasury instruments. As more fully described in Note XX, NFP A also has committed lines of credit in the amount of $20,000, which it could draw upon in the event of an unanticipated liquidity need.

Alternatively, the nonprofit could present tables (see 958-210-55-8) to communicate the resources available to meet cash needs for general expenditures within one year of the balance sheet date.

Cash Flow Statement Presentation

A nonprofit can use the direct or indirect method to present its cash flow information. The reconciliation of changes in net assets to cash provided by (used in) operating activities is not required if the direct method is used.

Consider whether you want to incorporate additional changes that will be required by ASU 2016-18, Statement of Cash Flows–Restricted Cash. If your nonprofit has no restricted cash, then this standard is not applicable.

You can early implement ASU 2016-18. (The effective date is for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2018.) Once this standard is effective, you’ll include restricted cash in your definition of cash. The last line of the cash flow statement might read as follows: Cash, Cash Equivalents, and Restricted Cash.

Effective Date of ASU 2016-14

The effective date for 2016-14, Not-for-Profit Entities, is for fiscal periods beginning after December 15, 2017 (2018 calendar year-ends and 2019 fiscal year-ends). The standard can be early adopted.

For comparative statements, apply the standard retrospectively.

If presenting comparative financial statements, the standard does allow the nonprofit to omit the following information for any periods presented before the period of adoption:

- Analysis of expenses by both natural classification and functional classification (the separate presentation of expenses by functional classification and expenses by natural classification is still required). Nonprofits that previously were required to present a statement of functional expenses do not have the option to omit this analysis; however, they may present the comparative period information in any of the formats permitted in ASU 2014-16, consistent with the presentation in the period of adoption.

- Disclosures related to liquidity and availability of resources.