AICPA Consulting Standards – The Swiss Army Knife

By Charles Hall | Accounting and Auditing

In this post, I tell you how to use the AICPA Consulting Standards (Statement on Standards for Consulting Services). I will also compare AUP engagements with consulting engagement options.

Are you ever asked to perform unusual engagements? Such as a report of a city’s water loss. Or a review of billing and receipts internal controls. Or maybe a test count of widgets in the Macon, Georgia warehouse.

When such requests are made, you might wonder “what professional standards should I follow?” Often the answer is the AICPA Consulting Standards.

AUP or a Consulting Engagement?

Regarding new and unusual engagements, I am sometimes asked, “Should this be an agreed-upon-procedures (AUP) engagement or a consulting engagement?”

My answer: It depends.

Allow me a moment to compare AUPs with Consulting engagements, and then I’ll explain what the decision hinges upon.

Agreed Upon Procedures Engagement

First, consider the AUP option.

AUPs are mainly composed of the following:

- Procedures

- Findings

You perform the procedures in relation to assertions made by a responsible party.

An example of a procedure and finding follows:

Procedure – Agreed all January 2020 disbursements greater than $20,000 to checks that cleared the bank statement; compared the payee on each check to the payee per the check register.

Finding – All check payees agreed with the exception of check 2394 for $45,000. The payee for this check was I. Cheatum, and the check register reflected a payment to King’s Supply Company.

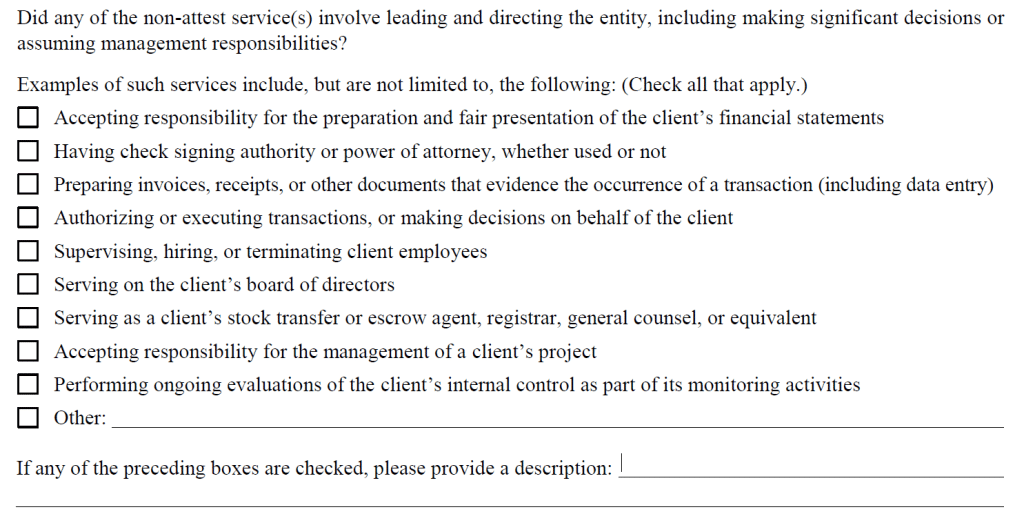

Additionally, independence is required.

CPA Consulting Engagement

Second, we’ll consider the consulting engagement option.

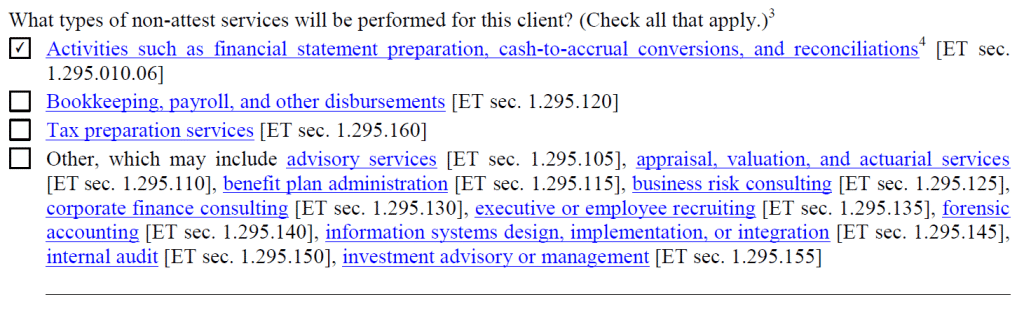

A consulting engagement is less precise than an AUP and does not necessarily follow the procedures/findings format. There are no specific reporting standards for a consulting engagement, so a CPA can more easily design the engagement to meet various needs. The consulting standards are more flexible than the attestation standards. And this flexibility enables you to be more creative in designing the engagement.

Assertions by a responsible party are not required under the consulting standards.

Moreover, independence is not required.

A consulting report might address the following:

- Reading of minutes

- Interviews of individual employees

- Flowcharting of internal controls

- Summary of production statistics

- Narrative of business goals and enterprise risks

As you can tell, there are no procedures and findings (though you are not prohibited from doing so). Most CPAs usually perform AUPs when there are specific procedures.

The Best Option

So which is better? An AUP or a consulting engagement?

I’ll say it again: It depends. On what? Third party reliance.

Consider the following:

- Will there be external parties (e.g. creditors) placing reliance on the report?

- Is the purpose of the report to add credibility to the information (by having the CPA attest to procedures and findings)?

If the answer to either of these questions is yes, then consider the AUP option. Why? The Attestation Standards–the guidance for AUPs–are more defined and rigorous. And AUP procedures tend to be more specific than those in a consulting engagement.

If no third party reliance, then a consulting engagement may be the better option. Always ask, “Who will receive the report?” You need to know who will read and potentially place reliance upon the report. Then design the work product accordingly.

Litigation Exposure

Are consulting engagements riskier than AUPs? Generally, yes. At least, in my opinion.

The safer option is to perform an AUP. In such engagements, you are asked by the client to perform particular procedures. This specificity lowers the risk of potential litigation as it relates to your work product. The flexibility of a consulting engagement, while helpful in designing creative deliverables, can be riskier because of the lack of specific client requirements.

Now, let me provide you with an overview of the Consulting Standards. As you read this primer, consider how flexible the guidance is.

AICPA Consulting Standards Primer

You might call the AICPA Consulting Standards the CPA’s Swiss army knife. Why? Because of the diversity of services you can perform.

What services fall under these standards?

The consulting standards specifically address six areas:

- Consultations – e.g., reviewing a business plan

- Advisory services – e.g., assistance with strategic planning

- Implementation services – e.g., assistance with a merger

- Transaction services – e.g., litigation services

- Staff and other support services – e.g., controllership services

- Product services – e.g., providing packaged training services

CPAs often provide consulting services such as the following:

- Consultations with regard to complex transactions

- Fraud investigation services

- Internal control services

- Bankruptcy services

- Divorce settlement services

- Controllership services

- Business plan preparation

- Cash management

- Software selection

- Business disposition planning

Now, let’s review the characteristics of consulting engagements.

Characteristics of a Consulting Engagement

The characteristics of a consulting engagement include the following:

- Generally nonrecurring

- Requires a CPA with specialized knowledge and skills

- More interaction with client

- Generally performed for the client (usually, no third party sees the information)

But, what are the workpaper requirements for a consulting engagement?

Consulting Workpaper Requirements

Consulting workpaper requirements are minimal. Nevertheless, documentation is always wise.

The understanding with the client can be oral or in writing (I recommend the latter).

The consulting standards do not require the CPA to prepare workpapers, but you should do so anyway. The workpapers are the link between your work and your report. Also, the general standards of the profession, contained in the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct, apply to all services performed by members. The general standards state:

Sufficient Relevant Data. Obtain sufficient relevant data to afford a reasonable basis for conclusions or recommendations in relation to any professional services performed.

By now, you’re probably thinking the Consulting Standards sound easy, I’ll bet the reporting requirements are challenging. Not so, my friend.

Consulting Reports

A report is not required, but if one is provided, the client and CPA determine the content and format. How’s that for flexibility?

No Opinion or Accountant’s Report

For consulting engagements, the CPA does not issue an opinion or any other attestation report.

Subject to Peer Review?

Are deliverables created under the Consulting Standards subject to peer review? No.

Where Can I Find the AICPA Consulting Standards?

Here are the AICPA Consulting Standards. They are only a few pages long.

AICPA Consulting Standards Summary

The Consulting Standards provide us with a breath of options, enabling you and I to craft services and reports in the manner desired by our clients. This is one Swiss army knife that I will continue to use.